The Brehon Laws, or to use their proper name Fénechas, was the native indigenous law system found in early medieval Ireland. The word Brehon comes from the Irish brithem, meaning jurist. These brithem essentially filled one of the many roles previously tended by the Druids and preserved and interpreted the laws that had been handed down orally through the centuries. These laws were eventually written down first between 650-750 AD in the old Irish period (The periods of the Irish language are roughly as follows: 400-600: Archaic/Ogham Irish, 600-900:Old Irish, 900-1200:Middle Irish, 1200-1650: Early Modern Irish). The texts only survive in 14th-16th cent manuscripts which are often incomplete or corrupted and early translations and publications are problematic.

I would like to stress however that just because these laws were written down, it does not mean that these laws were applicable across the entire country. Ireland at the time was politically fragmented but culturally homogeneous, with anything up to 150 separate kingdoms or túatha at any one given time. A number of these laws do however have a shared Celtic background with some aspects having indo-european beginning’s that can be traced. The Church eventually had an influence on many of the laws and vice versa, and the native laws also affected later English common law (which would eventually replace the native system).

There are many misconceptions on the internet in relation to the Brehon laws and how advanced they were (although there were many aspects that were advanced), with people often taking items out of context, so I hope to address some of this below. The system was compensation based unlike our modern system of incarceration, but it was heavily dependent on your social status and rank. Medieval Ireland was far from the equal, utopian society that people paint it as. The society was Hierarchical and inegalitarian. The laws clearly reflect this and show that Rank was important. Ergo an offence against a person of higher rank entails greater penalty than that of the same attack on someone of lower class. Native law never felt the same as roman law with all citizens being equal, canon law however was different.

I will cover this in greater detail below. First I will explain the makeup of the manuscripts themselves, two of the main schools of law and will then detail some of the material the laws cover such as status, slavery, sexual assault, status of women, fosterage and a number of other items. While this is no way an exhaustive list, it is a bit lengthy, so grab a cup of coffee and thank you for taking the time to read it. I hope you enjoy it and come away with a deeper understanding of the laws.

Canon, Glosses and Commentaries

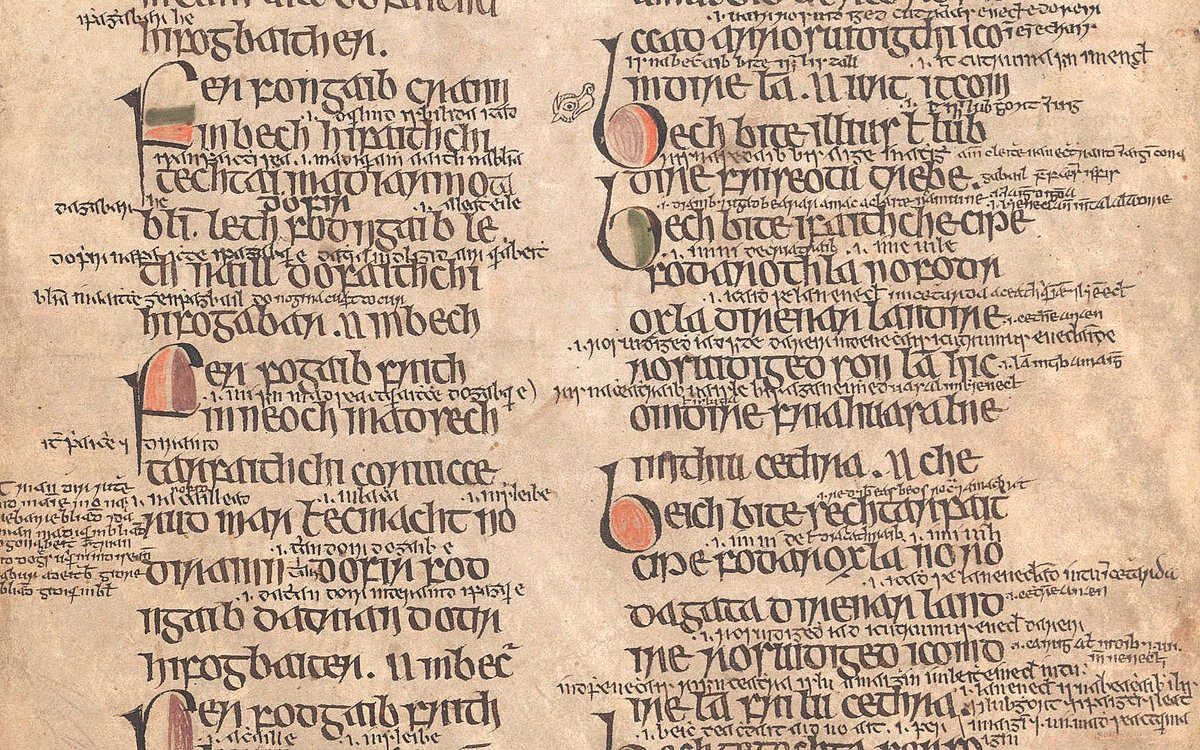

When looking at the manuscripts (like pictured above) you will notice writing between the lines and on the side. The main text in the center is the original law (canonical). The writing in between the lines of text are the glosses, added to update or comment on the law and then the writing in the margins are the later commentaries. These commentaries often show the difference between Irish laws and the common law that was starting to be introduced but can often be problematic due to errors in translation or misunderstanding on the part of the scribe. The typical dates of this material are roughly: Canonical: 650-750 AD, Glosses: 900 AD, Commentary: 1200 AD onwards

Cáin Laws

Another type of law found in these texts are Cáin laws. These laws were laws of ecclesiastical inspiration that were promulgated by secular kings and rulers over large areas i.e overkings (those in charge of more than one kingdom, with lower petty kings beneath them) would promulgate them. These laws were more focused on equality in some cases which breaks the whole “christianity ruined everything” fallacy that is usually attached to the Brehon Laws on the internet. The most famous of these laws were Cáin Adomnán and Cáin Phádraig, both focused on the treatment of non-combatants such as women, children and clerics during wartime.

Examples of two of the legal schools:

- Seanchas Már (great tradition/great collection): The book is a compilation of older native law, codifying it. The native laws had become popular again in later centuries as a way of combating the common law. The book of Seanchas Már has a Pseudo-historical prologue, giving saint Patrick’s seal of approval on the laws and mentions that these laws were told to him by Dubthach maccu Lugair (the ollamhfilid/ chief poet of Ireland). This was to legitimise these laws in the eyes of the church to remove any inclination of pagan practice (essentially saying if it was good enough for Patrick, its good enough for everyone else). It 48 tracts dealing with: status, water rights, cats/dogs/bees and beer among other things.

- Nemed: These are laws pertaining to privileged people, the Áes Dána, the people of skill/ crafts such as blacksmiths, filid*, goldsmiths etc. these texts however are more obscure in terms of language.

*The Filid (meaning Seer) were the professional class of poets (essentially a repackaged form the druids when they lost power), second only to the king in terms of status and were one of a number of things needed for a petty kingdom to be considered a tuath. The Filid consisted of seven grades and these Grades were determined, in part, by the number of stories and poems they had to know by memory. Their status was a point of contention over the years, with Saint Colum Cille returning from Scotland to speak on their behalf at the Convention of Druim Cett (575 AD). One of the reasons for the convention was an attempt to censure the filid due to their extravagant demands and lifestyle. It ultimately had no effect on them and their high status remained unchecked for centuries. Not to be confused with Bards who were a later emergence and lower class. The filid did however more or less merge with the bard class in the later middle ages as Gaelic society went into decline until their ultimate demise post battle of kinsale aand “the flight of the earls”. The Tract Uirechecht na ríar, focuses on grades of filid and how much material they are required to know.

Status inside and outside the Túath

As I mentioned above, Ireland was divided into anything up to 150 kingdoms at any one time from the 5-12th centuries. Unless your neighbouring túath had a friendship treaty (Chairdeas) with yours you had no status outside of your own túath. You were either considered a person of legal standing (Aurrad) or an outsider (Deorad). Being an outsider you were often considered an Ambue (non-person). Being an Ambue it was not considered an offence for someone to refuse to pay your body fine (erec) if they injure you. So essentially there were no rights for ordinary freeman outside his territory. Except on military service, oenach,or on pilgrimage. Nemed people or clerics were not included in this.

The laws mention a number of different types of outsider including the Cú Glas (Grey dog): This was an outsider from overseas. He had no legal standing, but if marrying into túath and recognised by woman’s kin, he gets half her honour price. He cannot make contracts without her permission and she is libel for debt/fines incurred by him. He also has no say in rearing the kids. Another was the Deorad Dé (exile of god). This was essentially referring to travelling monks or peregrini. These had Special privileges such as the fact their word cannot be overturned by king. Another, the Murchoirthe (one thrown up by the sea/castaway). May have been set adrift (a punishment where someone was placed in a boat with no oars and set adrift). If taken in is only 1/3 his masters honour price.

Lóg n-enech/ honour price/ price of the face

The honour price is the amount due for serious offences against you or your honour such as: murder, satire, injury, refusal of hospitality (or giving the wrong food, such as giving honey in the porridge of a lower class person).

Uraicecht becc (small primer), Míadslechta (passages concerning rank) and Críth Gabhlach (the forked purchase) are a few of the texts dealing wih status. Críth Gabhlach informs us of the range of honour prices and these are dependent on you social status. This is the price a person would have to pay if they caused an offence against you:

- 14 cumals (42 milch cows) for a provincial king.

- Yearling heifer for a fer midboth (man of middle huts, semi independent youth)

- Aithech fortha (substitute churl): This was a person of lower status to allow some sort of equality and to allow someone of low status and allows them to sue a king. the aitheach was essentially a whipping boy to balance the scales a little

- In practice though it was mostly concerned with those that were (1) Nemed and those that were (2) Those that were Sóer (free) or Dóer (Unfree)

- Children up to age 7 are an exception. Same hp as a cleric regardless of their social status.

Currency

1 milch cow = 3 Cumhal (female slave) = 1 ounce of silver

Legal acts were linked to your honour price so you were unable to make a contract for amount greater than your honour price. You could not go surety for greater than your Honour price. Any evidence given is weighed according to your status which means that if someone of higher status gives evidence against you, then they are automatically believed over you. This is known as overswearing.

Overswearing: “any grade which is lower than another is oversworn,any grade which is higher than another overswears” An over swearing can can refute the swearing of an inferior or can fix guilt on an inferior –Di Astud Chirt agus dlighid.

Change in status

It was possible to rise or fall in status or even become nemed. If you were demoted your family did not suffer (wife and son honour price remained the same) Breithe crolige says: “For the misdeed of the guilty should not affect the innocent”.

If someone could acquire enough wealth to support clients. Neither him/his son can become a lord but grandson can become Aire déso (lord of vassalry). This has a 3 generation rule similar to the fili/ banfilid.

Fingal/ Kinslaying

So what are the pitfalls of this compensation based system? They can be best illustrated by looking at the crime of kinslaying. This was especially frowned upon as the compensation system, which required payment from not only the transgressor, but also his kin, meant that the whole system fell apart with the act of kinslaying. Bloodfeuds in this instance would create a never ending cycle within a kin group with no possible way of paying fines, with each person subsequently committing Fingal/kinslaying. Killing was usually atoned for by the kin of the person who had been killed. A fort in which fingal was committed could be destroyed with impunity. There are a number of Annal entries relating to fingal and a few literary examples (such as Fingal Ronán and Aided Óenfhir Aífe).

Slaves

Slavery is usually thought of as something that the Vikings introduced to Ireland but in truth we had been well practised at for centuries. The most common names for slaves in Irish were mug for male and cumal for female slaves. Cumal was also widely used as a unit of value. These could either be prisoners of war or debt slaves. The legal treatise Di Astud chirt acus dligid is against the release of slaves. Includes it among things that would make corn, milk and fruit to fail. Slaves = lords prosperity. The release of slaves was seen as an Immoral and antisocial act that is prone to supernatural retribution (similar to Gáu Flathemon/ Kings injustice which causes the same phenomenon in terms of weather and crops turning against them).

Status of women

The status of women in medieval Ireland is one of the most misinterpreted and misquoted things on the internet in relation to Brehon laws. The internet would have you believe that Ireland was a utopia for women and that they could fight and own their own property. This is not exactly the case (I will add a caveat that they were afforded some things which were unique in the context of Europe at the time, such as attitudes towards sexual assault, divorce and in certain special circumstances the right to own property). As a whole women were defined as being “legally incompetent “ along with children and mentally ill or insane people. By and large they could not make any contracts without a legal guardian*.

*Old Irish Díre-text :“Her father has charge over her when she is a girl,her husband when she is a wife, her sons when she is a widowed woman, her kin when she is a woman of the kin (no other guardians), the church when she is a woman of the church (a nun). She is not capable of sale of purchase or contract or transaction without the authority of her superiors” (c.f indian Laws of Manu that are almost identical).

There is a huge discrepancy between literature and reality when it comes to women i.e Queen Medbh being the real ruler of Connacht and king Ailill turning a blind eye to her promiscuity. No mention in annals of female political or military leader but there are mentions of warrior women in literature but no historic examples of note (in Ireland) to back up the claim.

Banchomarbae (female heir)

This is an exception in terms of women having rights and the thing that is most misinterpreted in terms of women owning property. (There are counterparts in the Torah (tirza) and also Indian parallels). The memes and false info circulating always mention that women could own their own property. This was however VERY rare. This was only in the case where a father died with no male heirs. Her children could not inherit the land after her death (it returned to the fathers kin) and she also only still had very limited legal capacity in terms of making contracts and still had a relatively small honour price. Women could however also be nemed (privileged) We see examples of Bansáer (wright), Banliag tuatha (woman physician/ midwife), Bandeorad (female hermit) mentioned in the laws.

Offences against a woman

An offence against a woman is usually considered a crime against her guardian (who would have a higher honour price). The church made it a bigger offence with the introduction of Cáin Adomnáin. This meant that the Murder of a woman could mean losing a hand and foot, being put to death and your kin having to 7 cumals. Cáin Adomnáin/ lex innocentium was introduced by Adomnáin, the 9th abbot of Iona. It was promulgated first at the synod of Birr in 697 and was aimed at making it a serious offence to kill non-combatants especially women, children and clerics. It was an update of the earlier Cáin Phádraig which aimed at preventing the killing of clerics. It was endorsed by over 90 kings and bishops from Ireland and Scotland. If a woman committed murder, arson, or theft from a church, she was to be set adrift in a boat with one paddle and a container of gruel. This left the judgment up to God and avoided violating the proscription against killing a woman.

A pregnant woman could steal food without penalty if she had a craving.

Divorce

A woman could Divorce (Imscarad) if husband rejected her for another woman, fails to support her, spreads a false story or satire or if he tricked her into marriage by sorcery. He is allowed to strike her to correct he, but she can leave if it leaves a blemish. If he is impotent/ too fat to have sex/gay or sterile, this is also grounds for divorce as well as he becomes a cleric.

A man can divorce woman (listed in Gúbretha Caratnaiad) if she is unfaithful, if she induces an abortion or if she is a habitual thief. If she brings shame on his honour, smothers her child or if she “is without milk through sickness”, then these are also grounds for divorce.

There are also options to separate for a time for pilgrimage or if one is barren etc.

Rape or sexual harassment

There 2 types of rape listed in early laws: (1) Forceable/violent (forcor) and (2) sleth associated With drunkenness. Sleth is considered as bad as forcor, but there are circumstances where they have no redress. Married woman alone in a tavern cannot get compensation for Sleth. 8 types of women are not able to get compensation including adulterous women and a prostitute. If a man rapes a chief wife he has to pay the Full body price (Éraic), a concubine only requires him to pay half body price.

In terms of sexual harassment Bretha Nemed toíseach says the full honour price is to be paid for if kissed against will. A gloss on this mentions the shaming of a woman by raising her dress. Cáin Adomnáin states that the price is 10 ounces of silver for touching a woman or putting hands inside girdle or 7 cumals for putting hand under dress to defile. In these regards, the Brehon laws were very progressive.

Satire

The words for satire translate as “to cut” or “to strike”…. Showing how powerful it was. Satire was a powerful tool if used correctly and could be used to exert pressure but illegal satire required the full honour price payment and included things such as mocking through gesture, publicising a blemishcoining a nickname that sticks. Satire was believed to be so powerful that it could literally bring boils out on a person’s face or even have the power to kill.

“The poet said that he would satirise him for contradicting him and he would satirise his mother and father and his grandfather and he would chant upon their water so that fish would not be caught in it’s river mouths. He would chant upon their woods so that they would not give fruits unto their plains, so that they would be barren henceforth of every produce”.

Female satirists were especially feared and had freedom to move around whereever they wished. An excerpt from Longes Mac n-Uislenn (The exiles of the sons of Uisliu/ Deirdre of the sorrows) says the following: “and no person ever was allowed into that court except her foster father and her foster mother and Leborcham; for the last-mentioned one could not be prevented, for she was a female satirist”.

Fosterage

It was very common to foster children out at an early age. The bond between foster kids and parents can be seen through Intimate forms of language (like mammy over mother) being used for the foster parents instead of parents. E.g DATÁN for foster father is similar to daddy. Unusual in an Indo-European language. Fosterage served a number of fuctions such as creating bonds between families and providing education. Children were typically fostered down the social ladder and there were two types of fosterage: Altram serce: Fosterage for love/affection.For this, there was no fee involved and the child was usually from the mothers kin. Altram was the standard fosterage. A fee was paid dependent on status. There was a higher price for girls (commentary tells us that this was because they were harder to raise and less use in later life, the foster kids were responsible for the foster parents later in life and in their infirmity) . They also need attendants because they can’t be left on her own (c.f Fingal Ronán)

Cáin Iarraith “Law of fosterage fee” says the child must be maintained according to their rank. ( such as having salt,butter or honey in their food). The education received was both gender specific and status specific and the child could be fostered to multiple different people for learning different skills. Examples of this are as follows: Son of king/noble must be provided with a horse and clothing to the value of 7 Sét. He must be taught how to play fidchell, swimming and marksmanship. The Son of Ócaire must learn to look after animals, dry corn and chop firewood. The lowest fee wwas 3 Sét (ocaire) up to 30 Sét (Son of king), with 1 Sét more for girls of each rank

Sick Maintenance

Bretha Crólige (concerns sick maintainace) and Bretha Dian Chécht (concerns payment for injury) are two of the main tracts dealing with what happens if someone is injured. It goes as follows: for 9 days the injured person is cared for by kin.If death occurs in this time the full fine is to be paid. After 9 days a doctor is summoned to check on the person and if they are better you must pay for lasting blemish/disability. If not…sick maintenance (othrus) takes place if the doctor believes they will recover, but are bedridden. The injured Party brought to house of a third party and cared for. This house must be suitable for their status and also have the ability to support their retinue. B.Crolige says “There are not admitted to him into the house of fools or lunatics or senseless people or halfwits or enemies. No games are played in the house. No tidings are announced. No children are chastised. Neither men nor women exchange blows…No dogs are set fighting in his presence or in his neighbourhood outside. No shout is raised. No pigs squeal. No brawls are made. No cry of victory is raised. No yell or scream….”.

A substitute has to be provided to carry out the work of the injured party (unless nemed). An additional fine is to be paid if the injured party is married and can reproduce. This is known as the Barring of procreation. Some people such as a Druid, a Díbergach (outlaw) or a Satirist were only allowed the same level of sick maintenance as a bóire (lowest grade of freeman).

Thank you for taking the time to read to the bottom and I hope you enjoyed this. Don’t forget to like my page on facebook to keep up to date:

https://www.facebook.com/Irishfolklore/

Sources:

A further reading resource list can be found on Lora O Brien’s website with the specific blog post here

Guide to Early Irish Law by Fergus Kelly

Daniel Binchy’s translation of Breithe Crólige and Breithe Dían Chécht.

thanks for writing this. Had collected various tidbits of info over the years re the brehon laws but it’s good to have some of them corrected and to be made more aware of them. Very informative

LikeLike